Deleuze's On Painting: Seminar 4(a) - The Manual and the Digital

Seminar 4 continues an elaboration of the three “positions” of the diagram laid out in Seminar 3: Abstract—Figural—Expressionist. And it appears to do so by an increased emphasis on “position or placement,” the hand/eye tension, or the manual.

It may be useful then, to come in through Deleuze’s apparently off-hand reference to Leroi-Gourhan, which results in a kind of laughable possible future: a humanity with no hands only a single digit. (You know, for interacting with code!) This observation of Leroi-Gourhan’s also seems somewhat off-hand in Derrida’s Of Grammatology as well, but I think this merits closer examination. Why is Leroi-Gourhan always, when mentioned, treated somehow in passing, and always around this strange, Black-Mirror-like image of a deformed future “human”?

Also, who is Leroi-Gourhan?! And could it be that this reference to the loss of hands is something like a short-hand for something much more complicated going on around hands and mark-making? In our Gestures group we recently read his seminal, but largely under-examined, book Gesture and Speech. In it, he makes the case for a much deeper relationship between the hand (tools, mark-making) and the mouth (speech, language) as the evolving conditions for the development of the externalization of both function and adaptation. The question would be whether this larger assessment is undergirding Deleuze’s citation of the kind of limit case of code, where the hand is replaced by a kind of single digit for selecting binaries. And if so, does this give us a better understanding of what Deleuze thinks is at stake in the variable tension between eye and hand in painting? Or is Deleuze in some way already collapsing and reducing the function of the hand, even as he tries to use it to articulate these painterly positions? All we know at this point, is that he is now isolating three distinct arrangements of the eye/hand tension that correspond with the three positions of the diagram. (But not precisely, and we will have to return to this difference.) So for now we have just a speculative foray into the articulations of the hand:

I could develop a list of categories of the hand, make a start at it, give it a try. It’s pure conjecture at this point, but we’ll see whether this is confirmed later on. For starters, I’d like to make a distinction between the manual, the tactile, and the digital. (118)

But let’s stay with Leroi-Gourhan for a moment. First, it should be noted that for him the primary tension and coordination is not of eye and hand but of hand and mouth. The hand, increasingly adapted to extending and manipulating the material world, frees up the jaw for other usage, and particularly speech. (And it is only when the jaw transforms that the skull finds room for the brain expansion to follow!) So what of the eye? This is a complicated question, and would take more time to work through. But we should note two things. First, that the hand starts to make marks, as a visual function disarticulated from the functional need to processs materials or food. Second, the mouth, giving rise to language, is also eventually partially disarticulated from this function. First the hand takes on a certain level of abstract function through the pictogram, before the alphabet eventually harnesses the visual mark back to speech. Writing becomes something like the subordination of the hand to speech, while at the same time rendering speech a function of the coordination of the hand and eye. And so, after following the long evolutionary development of the poles of technics and language, Leroi-Gourhan is forced to go back and attempt to weave the question of Art back through these as a third pole. So the challenge would be to see whether this resonates with Deleuze’s more specific entry point, with the question “Why paint today?,” and his attempt to answer this in terms of the tension between eye and hand.

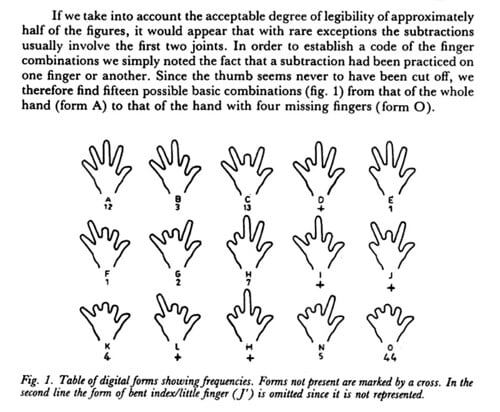

Before we can begin to approach the question of what happens to the hand in the digital relationship to code and Abstract Art, we should stay with one more apparent assault on the hand, from Leroi-Gourhan’s perspective, that might give us a more complex understanding of the (binary) articulation of language that Deleuze references here. And for that, we need to understand better the specificity of the hand. In “The Hands of Gargas: Toward a General Study,” from which we drew the image above, Leroi-Gourhan addresses the painted silouettes of hands, apparently missing different fingers, found in the cave of Gargas. The common interpretations reduce the hand either to a ritual site of mutilation through amputation, or one afflicted, as a kind of biological weak spot, by the mark of frost-bite. Both reduce the hand to a kind of accidental signifier, through its partial absence. But what Leroi-Gourhan points out, is that if you look at the particular arrangements of the hand, you see that they are actually grouped around a kind of facility of the hand to articulate itself in varying degrees of difficulty.

It is, in any case, perfectly possible, by bending the fingers and placing either the palm or back of the hand against the wall, to reproduce all of the mutilations at Gargas (21).

And any attention to the hand would show that there are particular arrangements that come easier than others. So rather than seeing these images as an act of violence against the hand, either from the social or the elements, we can see the hand as particularly suited to articulating without violence. And what we get is a whole range of possible arrangements. (Here we should remember that Deleuze wants to suggest that even the color wheel is conceivable as complex series of binary operations.) Without getting into to nuances, we should note that Leroi-Gourhan’s proposed interpretation still leaves us with the question of the relationship between code and painting:

A familiarity, like that of many hunting peoples, with the play of fingers as a silent signaling of the presence of game of one sort or another does not strain credibility. What is remarkable, if this hypothesis is valid, is their transposition of the hunting signals to the cave walls (34).

And so the question of art continues to pose itself as a question of the hand and its transpositions. (And we also now have something like a parallel to the case of Turner, who went from painting scenes of catastrophe to painting itself as a kind of catastrophe of the scene. Here we have something like the hand taking itself as the content or scene of an apparent catastrophe!)

Ok, the digression is threatening to become longer than the recap. The problem, of course, is that we still don’t have much to work with in Deleuze. We just know that he is now fleshing out his idea of the manual as a particular revolt of the hand against the eye in Abstract Expressionism, in light of the other possible “positions” of the diagram. As he says, the problem is that the hand can take many forms, and the need for a list of categories: tacticle manual, and digital. (How are we to think of these three? Part of a larger list?!) The manual, as the Expressionist turning of the hand against the eye begins to get some pushback from the participants, but what we can see is that it’s largely a question of stance or place. Pedagogically, its also a question of how we are taught to place ourselves in the shoes of the painter, and so they are pushing back in the name of another possible stance. But Deleuze wants to say that it amounts to the same thing. How do you assess your relationship to the painter or the painting when that is the very thing that the painter is pushing back against through the manual and the displacement of the painting away from the optical horizon? It hardly matters that the painting is then hung on a wall. This doesn’t it make it an optical problem, it simply makes the hands (or feet!) visible as a ground that makes the horizon unworkable.

By extension, then, at the opposite configuration of the diagram we find the hand reduced to the bare minimum, a digital finger that selects from the available elements a series of binary options. Of course, this doesn’t mean the hand is gone, it just means that the diagramatic force is carefully prescribed. What distinguishes the squares of a Mondrian from geometric code, or the work of a computer, is the subtle variation of vertical lines, that wind up generating a kind of virtual line as a ghostly diagonal. The minimal hand is able to gesture toward something that doesn’t appear to be on the canvas itself. And so, in a weird way we still have, “in the hand’s absolute subordination to the eye,” (118) a kind of disruption of the eye by the hand.

Let’s end with the third possible configuration of the eye/hand, the tactile, and as promised the discrepency that keeps these from mapping precisely onto the diagrammatic positions. The tactile, he says, is the hand subordinated to the eye. But again, we can see a gap emerging that Deleuze is struggling to articulate except by its absence. If even in the complete subordination of the digital something of the hand escapes, with the tactile we have a similar situation. On the one hand, he wants to just call it the (normal?!) subordination of the hand to the eye. But if we are to link this to the Figural, as the middle third-way, this doesn’t quite work. Because the figural is the place where this tension is most evident. Figural art, has the same problem as the other two: how does something of the hand challenge the eye. And so either the tactile has to mean this local battle against the contour, or it has to suggest what happens when this battle is lost and the figural collapses back into figuration and contour.There is a kind of semantic slippage that continues to make it difficult to line the categories up.

To put it another way, we could say that there is a strict parallel between Abstract—Figural—Expressionist and Digital—Tactile—Manual, in wich case we struggle to articulate the ways in which this doesn’t account for the catastrophe: “Clearly not; that’s not right,” he says (118). Or “the manual” always stands for this resistance to the subordination—across all three positions—in which case it’s not particular to Expressionism.

What is at stake in this besides a kind of sematic challenge? Maybe nothing, but maybe what we are seeing is that specificity of the hand itself, and its ability to move between these different configurations is itself one of the things that is at play here. And so we would be falling for a trap if we thought that, in becoming digital, the hand is just being amputated into a single finger. Or that the eye is eclipsed. As Deleuze keeps cryptically saying, we discover a third eye. But what is this, if not another possibility of the articulations of the eye as well? Are we not just finding a whole array of possible articulations of the body as a whole?